Communities have a say in the deployment of surveillance technologies, and Portland is proving it

The City of Portland in Oregon, United States, is building its Surveillance Technologies Policy together with its citizens. We talked to Hector Dominguez, Open Data and Privacy coordinator in Smart City PDX to learn why it is important to involve the community in the creation of such a policy, and get insights on how they are leading the participation process. The Surveillance Technologies Policy will provide guidelines and structure to the use and procurement of surveillance technologies, including implementing privacy impact assessments and effective public participation in governance and oversight.

What is at stake with surveillance technologies?

Surveillance technologies have the reputation of being intrusive in general, and there is a connection between surveillance technologies and abuses of civil liberties and civil rights. And that comes from a long way back: here in the US, in the 1960s or 1970s, recordings were used to wire-tape and target activists from the civil rights movement.

Some laws came out of the discussions that such events sparked. The Privacy Act issued in 1974 is a clear example. However, what stands out is that it is one of the only laws at the Federal level that regulates everything related to privacy in the US —and it is from 1974.

Here in the US, there have been bits and pieces of laws targeting privacy. However, there is not a general umbrella privacy law that is modern and adapted to the fast-evolving pace of technology. Nowadays, it is very easy to collect and mine personal information, because people and devices are interconnected. That allows parties to use and abuse personal information for commercial or public purposes. I think these vulnerabilities of privacy and civil rights and liberties are what people think of when they think about surveillance technologies.

The use of personal information for targeting and manipulating specific groups has multiplied in recent years because of the emergence of Artificial Intelligence, advanced predictive algorithms, and big data. Understanding exactly what the impacts of these technologies are is hard for people, and that requires specific emphasis from governments to communicate and be transparent about what is made with them.

One of the key aspects of the Human Right to privacy is that it allows individuals to have self-determination, and I believe that is a feature that any society should have. That is why we need to look into the current state of technology in general, and particularly of surveillance technologies when we are trying to understand how a person, a group, or a collective moves, behaves, or does things in general. Being mindful of that might create a healthier society as well.

Why must surveillance technologies be regulated? What path is the City of Portland following to do it?

They must be regulated to avoid abuses and harm, but also because setting clear norms is key to creating a government that people can trust. The regulation also means creating guidelines and processes to understand how decisions are made. It is not just about limiting what can or cannot be used, but also about clearly disclosing how and why technology is used. That is what we are trying to do with the surveillance technologies policy in Portland: we are trying to create all these layers of transparency first, and then, building on transparency, think about accountability and the measures that can be put into place when civil rights vulnerabilities occur.

Why did you find it necessary to engage communities in the creation of the surveillance technologies policy?

Right now, most cities in the world are very heterogeneous. So many different people live together, and not all of them relate to technology in the same way or have the same history with technology.

Here in the United States, there is a lot of history and intergenerational scars around the deployment of surveillance technologies, in particular in native and black communities. Black families descend from people who were enslaved and have lived under surveillance for generations. This puts them in a different position from people that have a clear skin colour, and they are often perceived differently in terms of being a threat, which ultimately causes mistrust.

Governments usually push towards doing things through technology, data, and information without realising what are the consequences (intended or not) of what is being done. However, technology goes beyond its field and reconfigures systemic issues that involve access to housing, economic opportunities, education, and jobs. Nowadays, because everything is becoming digitised, information is crucial, and so is understanding how that information is collected from people and used and giving voice and a meaningful level of participation to those who are impacted. That comes with many challenges, such as the need to clarify what technology can do or to communicate and create processes in which everybody can talk about the same things in a clear, straightforward, and understandable way.

Sometimes it is thought that people cannot understand technology because they do not have the technical knowledge to do so.

During my experience in the City of Portland, I have had the opportunity to witness how local organisations work with migrant communities. A local organisation called SUMA, for instance, works with migrants from Latin America that mostly speak Spanish. This organisation has been developing a curriculum for providing literacy training around privacy issues. In the meetings, which were joined mostly by women —a majority of them, undocumented and working in cleaning jobs— people were very savvy and knew what digital tools were available to them to connect to the digital economy.

Looking at another example: in my neighbourhood, there is a big community of Asian migrants —particularly Chinese families. Over the past year, there have been cases of violence against people of Asian descent, and one mechanism of resilience they used was WeChat. In this network everything is in Cantonese, it is built in a culturally appropriate way and it grows organically among the community. Last year, with the last administration in the United States, there was the intention to ban Wechat and some Chinese apps: but having done so would have meant cutting people out of the network for doing regular things. When that debate happened, we started thinking about how to support that community if the ban happened.

One last example. Across Portland, there are many Somali families, and many of them are illiterate. We have been also thinking about ways in which they can participate in technology even if they do not know how to write and read. If we want to serve these communities we need to understand what is the context, and talk to them or approach the people who are talking to them and try to understand what is happening. It is quite complex. On our webpage, we are starting to explore how to translate the information we publish to reach out to non-English speaking communities.

What is the roadmap you are following? How is the community engagement process being done?

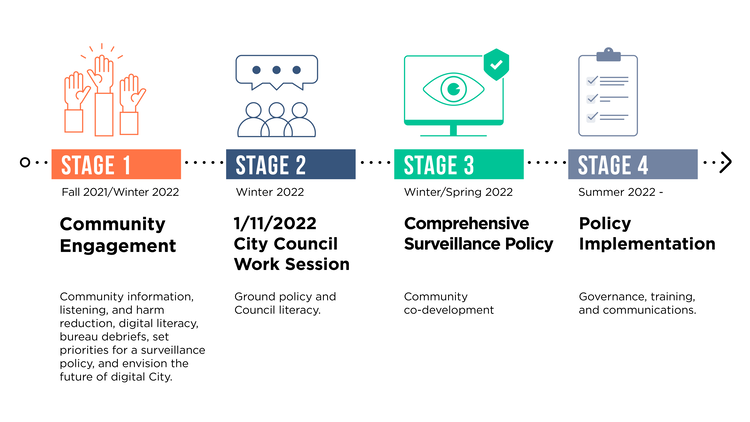

This has been a long process, and we see our own biases as well. All of the members of the Smart City PDX team have been to graduate school, and that is something we often get feedback on. We are used to a very academic language. However, we need to be mindful of the audience we are addressing, as we are talking to everybody, and change how we approach people. That process, which started in 2018, has been a long one: it started with work around open data and privacy, as well as some work on sensors for traffic monitoring. We are building on previous efforts and aligning them with the approach around equity Portland is developing at a city-wide level.

We started our work approaching our closest circle: academics and people who are already engaged in privacy, data, and tech, and that is how we developed our first policy, our privacy principles. From this group of experts that were already interested, we started drafting the fair recognition policy and approaching civil rights and civil liberty groups, working with specific demographics.

With the first experience, we learned that we needed to expand but we did not know how. We started a programme called equity community advisors, where we started paying people and organisers from the community to start telling us how to do things. We have a next iteration of the equity community advisors, which we call “community leads”. These four people help us figure out how to engage the community, and we have seen that we need to do more community education and simplify our language to reach everybody. We are trying to connect with all these different groups, which is difficult right now because there are many barriers. More consciously we are trying to identify the barriers that we encounter and say: how can we lower the barriers so more people can engage?

What is the profile and background of the community leads and how do you select them?

We select them through an open call. They do not have to be connected to technology or information. We just tell them: we are working on smart cities and technology. And we always try to find a balance between all the people who apply. Right now, they are quite diverse: three black women, and a queer person, all of them with different backgrounds, life experiences and perspectives.

What barriers have you already identified? How do these sessions take place, are they held online and also offline?

Before Covid-19 one of the barriers was the proper compensation of people’s time. Now everybody understands that compensation is needed; otherwise it becomes something more extractive and it is not fair.The engagement has been more of a challenge. Making information accessible to people in a way that they can understand it is one of the biggest barriers. When we are talking about AI, which is more of an abstract thing, we are still in the process of making it more accessible and letting people understand what an algorithm or an Automated Decision-making System is.

What would you recommend, from your experience, for other cities that also want to engage the public and lower the barrier for participation?

One is working on public trust. I guess that might look different in different places, and their history is always there. People may trust some aspects of the city, while they might hate some other services, or feel frustrated about them because in the past the city has failed to provide support, security or safety, or public spaces where kids can just go around. It is important to think about, as a city, how people can connect to do digital services or a programme that is going to make a change for them, and how their voices are going to be listened to. In Portland, we are having that conversation: people are investing their time, how are they going to be heard? How can they contribute in a meaningful way?

That can be challenging because of different opinions and perspectives that can conflict with each other, and sometimes we need to make decisions: how do we do it? Do we go to the basics? Do we go to digital rights? Our core values have to do with equity and trying to do that and do our best, as well as communicating with all the stakeholders involved in decision-making.

One of the barriers that we identified and are trying to resolve is providing economic incentives for participation to people. Properly compensating people's time when joining and engaging in an event.

We have found that there are existing policies that add too much bureaucracy and paperwork connected to collection of sensitive information, taxes, labour laws, and State ethics rules, and you can imagine that this could be really difficult for someone that is not familiar with them, at times including us, or that is facing any social stress in their lives. This issue is particularly complex, but we will be working with other teams to find alternatives.

Something very recent that we have all agreed is that we need to go where communities are and meet them there. The strategy of putting together centralised engagement events works for some, but not many. So, right now, we are having 8 different events on site with groups that range from houseless and people in recovery from drugs, recent immigrants where we are interpreting in Karen and Somali, and with a group of LatinX women called Guerreras Latinas on the limits of the City. It is harder to put together these events and we are finding many structural barriers for public participation, but the outcome has been very rewarding.

We are doing these last events this month in a pack schedule because we are closing public comments for the drafting of the Policy also this month (June 2022). One conclusion of this effort, so far, is that we need to have a permanent digital literacy program on Privacy and Data that goes beyond Digital Inclusion.

What have the results of these engagement processes been? What are the main concerns of the communities on these technologies, and how are you planning on incorporating them into your work?

There are so many concerns. One of the challenges is that we hear complaints in general, but the City government has jurisdiction only on specific aspects of civic life. The city is not in charge of schools, so we cannot do much about that. What we are trying to do is share and connect with other local jurisdictions and people who are competent in those matters, and that is another level of connection and engagement that we need to keep in mind.

In terms of concerns about surveillance technologies, sometimes people go through big narratives. We all build narratives to try to understand what’s happening in the world. And you know, sometimes those narratives are not necessarily true. For example, we have cameras that control the speed limit and take pictures of licence plates and then you get fined. Many people see the cameras (particularly non-documented immigrants) and think that information and their picture is going to be taken and the info will be mined by immigration and customs at the federal level. And then, because of that, they have a big detour that is almost 20 minutes longer than their regular travel distance. The problem is with transparency: the camera is there and you do not know how the info will be used. And that applies to many other devices that we do not even use, and to devices that are being used and no one knows about.

We need to communicate better and let people know that technologies can be empowering. But it cannot be like that if people are not participating in the selection or in identifying for what purpose do we need technology, and for how long, who is paying for all that information or what happens to that information after it gets collected. That is what we are trying to build with the policy: new processes for understanding impact, and hopefully, with that policy, we can get some more public interest, funding for these programmes and build more internal capacity.

Looking at the CC4DR and the cities in the world that are aligned with digital rights, equity, and justice when it comes to digital technologies, what would you recommend to cities that would like to follow a similar path? What would you make them mindful of or what challenges would you prevent them from taking?

One of the very important metrics that is hard to measure is public trust. We work very closely in collaboration with our office of Equity and Human Rights. When we approach the community, we are doing technology from a human rights, equity, digital rights, and digital justice perspective. How do we translate digital rights into something more formal to take digital rights into a digital justice legal framework? This is what we are trying to build and I think every local context has its way of developing public trust.

The other thing is engaging the internal City stakeholders as well as the external ones. Even if you think they might be in opposition to what you are doing: it does not matter. They need to be on the table. For instance, for the Surveillance Technologies Policy we have the police on the table, even though we understand the community and many members of our community do not trust them. We are trying to make sure we bring to every group that understands the situation, at least in these key policies.

We also work with other departments that can be impacted in the City: transportation, parks, emergency management and fire and community and civic life. We are trying to keep them as informed as possible on what we are doing, so that later when the policy happens that is not a surprise for them. Lastly, we are trying to understand how we can reach out to the middle layer, which involves supervisors and directors and provide them with targeted literacy. An important learning related to that has to do with the challenge of developing adult education tools and curriculum for people who have been out of school for a long time.

For more information, keep reading or visit Smart City PDX’s website